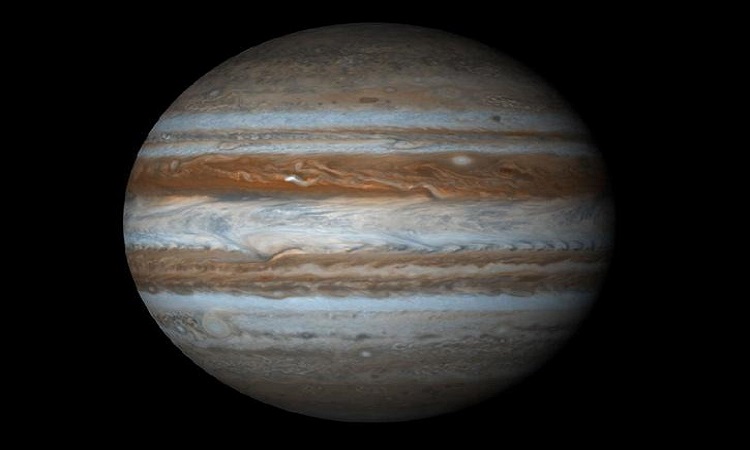

According to a study, Jupiter’s interior is home to the remains of sunken protoplanets while the future giant was expanding. These results come from the first clear view of the chemistry taking place beneath the planet’s cloudy outer atmosphere.

The formation of Jupiter

If Jupiter appears today as a huge swirling ball of gas, it began its life by accreting rocky material like all the other planets in the Solar System. Then, as the planet’s gravity pulled in more and more rock, its rocky core became so dense that it began to pull in large amounts of gas. It was mostly hydrogen and helium, in other words, crumbs left behind by the Sun.

There are two competing theories on how Jupiter managed to collect its initial rock material. One proposes that Jupiter accumulated billions of small space rocks similar to single boulders. The other proposes that Jupiter’s core was formed from the absorption of many planetesimals. Imagine large space rocks stretching for miles. However, so far it has not been possible to say with certainty which of these theories is correct.

And for good reason, Jupiter may be one of the most emblematic planets of the Solar System, but astronomers know very little about its internal functioning. We owe this lack of information to swirling vortices in the upper atmosphere and other storms acting as a filter beyond which one cannot go. These data are key to determining how this giant formed and evolved in the first place around 4.5 billion years ago.

Study tips the balance

In new work published in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics, Yamila Miguel and her team at Leiden University (Netherlands) have finally managed to break through this obscuring cloud cover. To do this, they used gravitational data collected by the Juno space probe. These analyzes made it possible to map the rocky material found at the heart of the giant.

The researchers found a surprisingly high abundance of heavy elements there. The latter have a stronger gravitational effect than the gaseous atmosphere. Analyzing this data ultimately allowed the team to map slight variations in gravity, which helped them see where the rocky material is on the planet.

According to the models, there would be an equivalent of eleven to thirty terrestrial masses of heavy elements within the planet (3 to 9% of its mass of Jupiter). For the authors of the study, this chemical composition suggests that Jupiter indeed devoured planets in formation, and not simple rocks, at the beginning of its formation. This voracious appetite eventually fueled its expansive growth.

This new study therefore supports the second theory mentioned above. If these baby planets had not been disturbed, they would have potentially acted as seeds from which smaller rocky planets like Earth could have developed.